On Christmas day the west opened their presents under pine trees and celebrated over large family meals an occasion which has been celebrated for thousands of years, far back into the first societies in Europe. However, for the Christians of Nigeria it was a time of fear and violence. Thirty died as a bomb went off near the Nigerian capital of Abuja in just one of many attacks across the country on the Christian holy day.

On Christmas day the west opened their presents under pine trees and celebrated over large family meals an occasion which has been celebrated for thousands of years, far back into the first societies in Europe. However, for the Christians of Nigeria it was a time of fear and violence. Thirty died as a bomb went off near the Nigerian capital of Abuja in just one of many attacks across the country on the Christian holy day.

The attacks come only two months after Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan described the group’s activities as a temporary setback for the state which would pass swiftly. Now, National police chief Hafiz Ringim has said “We are all scrambling to find our feet.” David Cook an expert on Boko Haram, says that “if radical Muslim violence on a systematic level were to take hold in Nigeria…it could eventually drive the country into a civil war.”

Nigeria is a proportionally huge state in Africa. One out of every four Africans is Nigerian and it is the seventh most populous country in the world. Its population is predicted by the UN to hit 730 million by 2100. Unlike many of its neighbours, it is not greatly poor either. It is classed as a middle-income country, with the world’s 37th highest GDP and a growth of above 8% per year. In 2006 it became the first African country to completely pay off its debts to the Paris club, numbering the western world’s most powerful economies and Russia. However, the populous and swiftly developing nation is divided evenly between Christians and Muslims split between the rich south and the poor north, and this tension threatens to derail Nigeria’s progress.

There is a perception that the Muslim north has been abandoned by the central, predominantly Christian, government in the south. The widespread corruption of government in the north and the poverty of the population there has driven youth towards Boko Haram in the same way as they had done to Islamists in Somalia, Afghanistan and the Arab Spring states. The attacks were further fuelled in 2009 when Boko Haram’s leader, Mohamed Yusuf, was shot dead whilst under police custody. Now Boko Haram has splintered into a loose collection of extremist groups operating out of the north, carrying out executions and assassinations of officials, security forces, Christian leaders and even moderate Muslim clerics and their own members attempting talks with the government. More recently this has spiralled into suicide bombings and the killings of 150 people in November in Damaturu, where they were said to have simply gone “through the Christian quarter of Damaturu and massacred anybody who did not know the Muslim creed.”

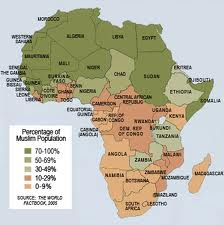

Nigeria is not the only place plagued by Islamic extremist attacks against Christians. There have been reports of hundreds fleeing Egypt to the US in the wake of the fall of Mubarak. Without the secular ideology of the military and security forces under his power, attacks on the Christian population have increased. Somalia can also be viewed in this light, as the predominantly Christian-ruled nations of Ethiopia and Kenya have entered the country to fight a group founded on Islamic extremism. South Sudan has gained independence as a largely Christian nation from the Muslim north. This north/south divide across sub-Saharan Africa is a hotbed of sectarian conflict between Christians and Muslims.

Nigeria is not the only place plagued by Islamic extremist attacks against Christians. There have been reports of hundreds fleeing Egypt to the US in the wake of the fall of Mubarak. Without the secular ideology of the military and security forces under his power, attacks on the Christian population have increased. Somalia can also be viewed in this light, as the predominantly Christian-ruled nations of Ethiopia and Kenya have entered the country to fight a group founded on Islamic extremism. South Sudan has gained independence as a largely Christian nation from the Muslim north. This north/south divide across sub-Saharan Africa is a hotbed of sectarian conflict between Christians and Muslims.

These differences have always been stoked by the relative wealth of Christians in Africa compared to the Muslim population in more mixed countries, a status created by the old European colonial powers. Although this difference is to some extent negated in the much more significantly Muslim Arabic north coast, fuelled by their oil revenues, it has continued to be a source of bitterness and conflict across central Africa. In times of poverty and conflict, the youth are drawn towards anything which can make their lives more regimented, meaningful and directed, and extremist Islam and to some extent Christianity can often provide this comfort.

However, they provide comfort in an ideology which promotes the destruction of those different and without the direction of their God. Faced with hundreds of others willing to defer moral authority to a single individual promising them riches, unity and eternal bliss, many are willing to join and take up arms against unarmed civilians to clutch for those promises. Driven by an intellectual elite who themselves have become disenchanted in a system in which their beliefs are marginalised, these conflicts will become worse until the reasons behind them are broken down. But for every gunshot and every bomb, these underlying causes for the thousands who flock to Islamist groups grow more serious and more difficult to fix.

This is the crisis Nigeria, and sub-Saharan Africa in general is facing on top of everything else they have to face from poverty to drought and starvation. These are the conflicts which the front page news often forgets to mention, and the western powers pass over in their military efforts. But as France and the US involve themselves in Somalia, and US advisers move to Chad to face the Christian extremist Lord’s Resistance Army, this may be the new battlefield in international interventions in the post-Iraq world.

Originally published on The Third Opinion.